VIGILANTES

In the earliest days of settlement in the far west, duly authorized law enforcement was too often inadequate and unreliable. The frontier drew adventurers of all sorts, both lawless and law abiding, and the dividing line between the two was often hard to distinguish.

Vigilante organizations flourished, and depending on your point of view they were either civic-minded volunteers dedicated to keeping the peace… or lynch mobs worse than the criminals they brought to a rough and ready justice.

San Francisco – First Committee of Vigilance

San Francisco – First Committee of Vigilance

IMAGE:By Mary Floyd Williams, History of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851: A Study of Social Control on the California Frontier in the Days of the Gold Rush. University of California Press, 1921, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2685888

San Francisco was twice under the rule of a vigilante committee, the first beginning on June 9, 1851. On that date 103 prominent citizens signed a formal declaration stating “We are determined that no thief, burglar, incendiary or assassin shall escape punishment, either by the quibbles of the law, the insecurities of the prisons, the carelessness or corruption of the Police, or the laxity of those who pretend to administer justice.” The Committee ultimately grew to 700 or more members.

The day following the declaration a man named John Jenkins was hanged by the Committee for theft of a safe from a local business, a crime at that time punishable by death in California. The Committee continued in operation for approximately three months, during which time it hanged a total of four people, whipped one, deported fourteen to Australia, ordered fourteen to leave California, handed fifteen over to public authorities, and discharged forty-one.

Although the Committee formally disbanded in September 1851, the leadership of the group continued to meet and ultimately formed the nucleus of the next Committee of Vigilence, which came into being about five years later.

San Francisco – Second Committee of Vigilance

On May 14, 1856, San Francisco’s second Committee of Vigilance was reorganized, using a constitution similar to that of the first Committee. This reformulated group addressed not only civil crimes, but political corruption as well.

The precipitating event was a duel between James P. Casey, newly appointed to the city board of supervisors, and James King of William, a newspaper editor. King had published an article in the Daily Evening Bulletin stating that Casey had once been sentenced to the State penitentiary at Sing Sing, and the duel resulted; King was killed.

Membership in the 1856 Committee was larger than that of the 1851 Committee, at its height claiming over 6000 members. A total of four people were executed by the Committee before it again disbanded on August 11, 1856. This time the Committee created a formal successor, the People’s Party, which remained active in San Francisco politics until 1867, and eventually merged into the Republican Party.

Virginia City – 601 Committee of Vigilance

Virginia City – 601 Committee of Vigilance

The notation of “601” is commonly taken to mean “6 feet under, 0 trials, 1 rope”, although the origin of this explanation of the name is unclear. 601 vigilante organizations sprang up throughout the late 1800s in various western communities to deal with lawlessness (and sometimes to perpetrate it). Bodie, San Luis Obispo and Truckee (California) all had organizations using this designation.

The best known and perhaps original ‘601’ was, however, in Virginia City, Nevada. The organization first emerged on the night of March 24, 1871. One Arthur Perkins Heffernan was being held in the county jail after having killed a man in cold blood at the bar of the town’s principal hotel. A group of masked men broke him out of the county jail and hanged him. The next morning the coroner found the body with a note inscribed “601” pinned to its shirt, and thereafter the organization was known by that name.

Only one further hanging was done by the Virginia City 601, that of one George P. Kirk, who was hanged on July 18, 1871. A convicted murderer from out of state, Kirk had been warned off by the 601 but returned to Virginia City thereafter and was executed.

Although the 601 was rumored to be still in existance for years afterward, no further activity took place and the organization passed into legend.

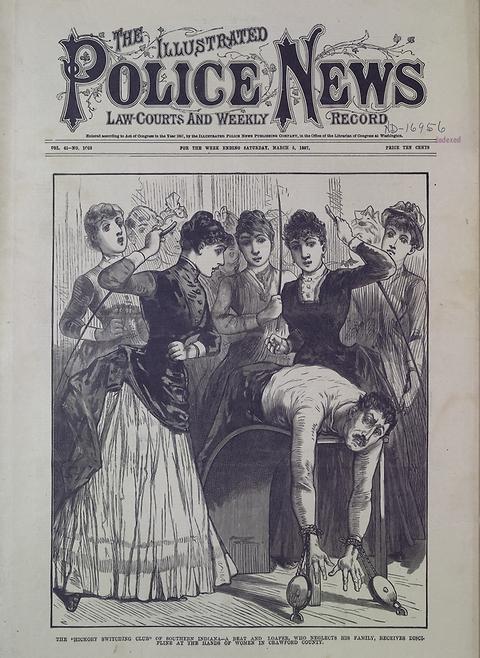

Virginia City – Amazonian 601 (Women’s Committee of Vigilance)

Virginia City – Amazonian 601 (Women’s Committee of Vigilance)

IMAGE: Courtesy of University of Minnesota, Children’s Literature Research Collections

Not all vigilante groups were male, or even co-ed. On July 2, 1871, the Territorial Enterprise reported formation of an all-female group known as the Amazonian 601, established to combat wife-beating.

OUTLAWS

Dozens of outlaw gangs terrorized the western half of the United States from the middle of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th, committing daring bank and train robberies, rustling cattle, and holding up stagecoaches and their passengers. The names of most of these gangs have faded into history, but a few have achieved lasting fame, due in part to the influence of the popular press of the day. One series of interrelated outlaw gangs in particular stands out.

It began in Lawrence, Kansas, a little town about a hundred miles south of the Nebraska border on August 21, 1863.

Quantrill’s Raiders

Quantrill’s Raiders

William Clarke Quantrill had begun his life of violence in 1856 with the murder of a man in Illinois. He was eventually released, but thereafter became a drifter and an all-around undesireable, ousted from one community after another for theft, gambling, and cattle rustling.

He fell in with a gang who roamed Missouri and Kansas kidnapping runaway slaves for reward money, and eventually became a Confederate sympathizer. He served briefly in the Confederate Army under General Sterling Price, but deserted in 1861 to form his own ten-man “army”, a pro-Confederate guerrilla organization. In 1862 Cole Younger and Frank James joined the group, which eventually numbered over 450 men. Jesse James, then sixteen, joined in 1864.

In 1863 Quantrill’s Raiders, as they came to be known, descended on the border town of Lawrence, Kansas, sacking the town and killing 183 men and boys. Union troops retaliated, setting fire to a swath of Missouri land bordering Kansas in order to deprive the raiders of food and sustenance. The gang then rode south to Texas, where they joined up with Confederate forces. Quantrill and his men quarreled, eventually breaking up into a number of smaller bands. Quantrill himself led a band north to Kentucky where he was ultimately captured and killed in 1865 by Union forces.

James-Younger Gang

James-Younger Gang

In 1864, a teenaged Confederate by the name of Jesse James joined the Raiders to be with his brother, Frank. When the war ended, the James brothers and a few other Quantrill’s Raiders remained together and eventually turned to armed robbery.

On December 7, 1869, Jesse James, together with his brother and other members of the Raiders robbed a bank in Gallatin, Missouri. A legend was born when, six months after the robbery, Jesse sent the first of a long series of letters to John Newman Edwards, editor and founder of the Kansas City Times and a Confederate sympathizer. In that letter the young rebel asserted his innocence and Edwards took up his cause, presenting Jesse as a modern-day Robin Hood and emblem of the undying courage of the defeated Confederacy.

Shortly thereafter the James brothers joined with Cole Younger and his brothers, forming the famous James-Younger gang. This group of disaffected former Confederates set off on a career of daring bank and stagecoach robberies that stretched from Iowa to Texas, and from Kansas to West Virginia. In July of 1873 they added train robbery to their repertoire. The gang wreaked havoc for another three years until a robbery in 1876 during which the Younger brothers were captured and many of the rest of the gang killed. Only the James brothers escaped.

Jesse recruited a new gang in 1879, but the members were not hardened guerrillas and the gang quickly fell apart. Jesse and Frank returned to their original home in Missouri, continuing their life of crime with the aid of a few hand-picked men. In 1882, Jesse was ultimately shot in the back by one of his own men. In an ending worthy of the dime novels in which he frequently appeared, he was immediately lionized as a folk hero in the popular press nationwide.

Dalton Gang

Dalton Gang

The Dalton Gang was a clear demonstration of the very thin line between lawmen and outlaws in the days of the wild west. The Dalton brothers were cousins to the outlaw Younger brothers who formed the nucleus of the James-Younger Gang. However, under the influence of the oldest brother, Frank, the three younger Dalton boys– Grat, Bob, and Emmett– were initially lawmen. They rode with Frank when he was a Deputy U.S. Marshal, but when he was killed on duty in 1888 his younger siblings turned to crime.

For four years the gang carried on a series of bank and train robberies, primarily in Kansas and Oklahoma, a la the James-Younger gang. Bob Dalton, one of the middle brothers, was obsessed with surpassing the feats (and fame) of Jesse James, and hatched the scheme of robbing two banks at the same time.

They chose the C.M. Condon & Company’s Bank and the First National Bank on opposite sides of the street in Coffeyville, Kansas. On October 5, 1892 they made their move. A fierce gunbattle ensued; at the end of it three townspeople were shot and the town marshal was killed, but four of the gang were dead also. Only Emmett Dalton survived, saved from a lynch mob only because with 23 gunshot wounds he was not expected to live. Yet he managed to recover, was pardoned after 14 years in prison, and went on to become a real estate agent, author and actor.

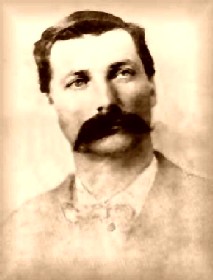

Doolin Gang (The Wild Bunch)

Doolin Gang (The Wild Bunch)

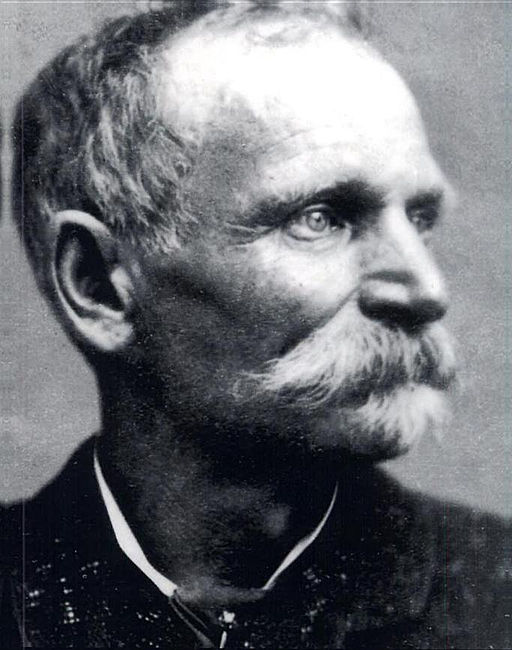

IMAGE: Bill Doolin. Courtesy of LegendsOfAmerica.com

The Doolin and Dalton gangs were also interrelated. Bill Doolin, founder of the Doolin gang, was a member of the Dalton gang for some years, while Bill Dalton (a middle Dalton brother) rode with the Doolin gang rather than with his own brothers.

Like the Daltons, the Doolin gang specialized in bank and train robberies, primarily in Oklahoma, beginning in 1892 and ending in 1896 with the death of its founder, Bill Doolin. For the four years it existed, the gang exhibited a violence and recklessness unparalleled in the old west, standing off 14 deputy U.S. marshals in Ingalls, Oklahoma in a gunbattle that ended the lives of three lawmen and two bystanders, with many wounded on both sides.

All eleven members of the gang met violent deaths in gun battles with lawmen, and only two lived past the turn of the century.

Belle Starr Gang

Belle Starr Gang

IMAGE: By Wolfgang Sauber (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Myra Maybelle Shirley Reed Starr was by all accounts a fiery and reckless teenager when she encountered Cole Younger. Perhaps “re-encountered” would be more appropriate, as she had known both the Younger brothers and the James brothers growing up in Missouri.

She was married at the time to Jim Reed, later an outlaw himself. Accounts differ; some say the child born to Belle in 1868 was Younger’s daughter, others that she was Jim Reed’s child. Whatever the truth of it was, she and Jim Reed had one more child together before he was killed in 1874. Belle later married a Cherokee man named Sam Starr, and when he in turn was killed in 1886 she again remarried, this time to a relative of Sam Starr by the name of Jim July Starr. All three of her husbands were outlaws, as was Belle herself.

Her lawless career was less colorful than those of her male counterparts, however. Her primary criminal activities were fencing stolen goods and harboring rustlers, horse thieves and bootleggers from the law. She never killed anyone, and though warrants were issued for her on charges of theft and robbery she was only convicted once, for horse theft; she served nine months at the Detroit House of Corrections in Detroit, Michigan.

She became famous as the “Outlaw Queen” after her story was picked up by Richard K. Fox, publisher of dime novels and the National Police Gazette, a magazine featuring pin-ups, sports news, and tabloid true-crime stories. On February 3, 1889, two days before her 41st birthday, Belle Starr was ambushed and killed, some say in retribution for other unknown crimes. Her murder was never solved.

OTHER GANGS, INDEPENDENTS AND COALITIONS

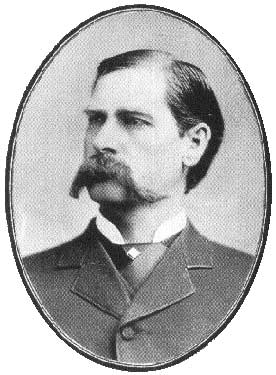

Clanton Gang, the Earp Brothers, and the Gunfight at the OK Corral

Clanton Gang, the Earp Brothers, and the Gunfight at the OK Corral

In 1881 the term “cowboy” was considered a synonym for “rustler”; legitimate cowmen were known as cowhands, drovers, stockmen, or ranchers. In all, an estimated 200-300 “cowboys” were operating in the area around Tombstone, Arizona, mostly rustling stolen Mexican beef.

Hence when the name “Cowboys” was given to Tombstone locals Billy Claiborne, the Clanton brothers Billy and Ike, and the McLaurey brothers Tom and Frank, it was not intended as a compliment. Nonetheless, the Cowboys were landowners and they spread their money liberally around town, so they enjoyed a certain amount of credibility locally.

By contrast, when lawmen Virgil, Morgan, and Wyatt Earp and their colleague, Doc Holliday, arrived in Tombstone on December 1, 1879, they were viewed as carpetbagging Northerners by some. Holliday in particular was suspect; he was believed to be a killer and was known to associate with a reputed stage coach robber. The distinction between law-abiding and outlaw was sometimes difficult to make.

Inside of two years, Virgil became City Marshal, and Morgan and Wyatt became Special Policemen. On April 19, 1881 the Tombstone city council passed an ordinance that prohibited carrying a deadly weapon in town. As marshal, Virgil was charged with enforcing the ordinance.

The Cowboys refused to surrender their firearms, and on Wednesday, October 26, 1881, the deadly Gunfight at the OK Corral ensued. In 30 seconds at least 30 shots were fired, some within 6 feet of the other side, and at the end Billy Clanton and both McLaury brothers were killed.

In an ironic reversal of roles, Ike Clanton subsequently filed murder charges against the Earps and Doc Holliday. For a time, it was unclear which would be judged on the wrong side of the law, but in the end the lawmen were exonerated.

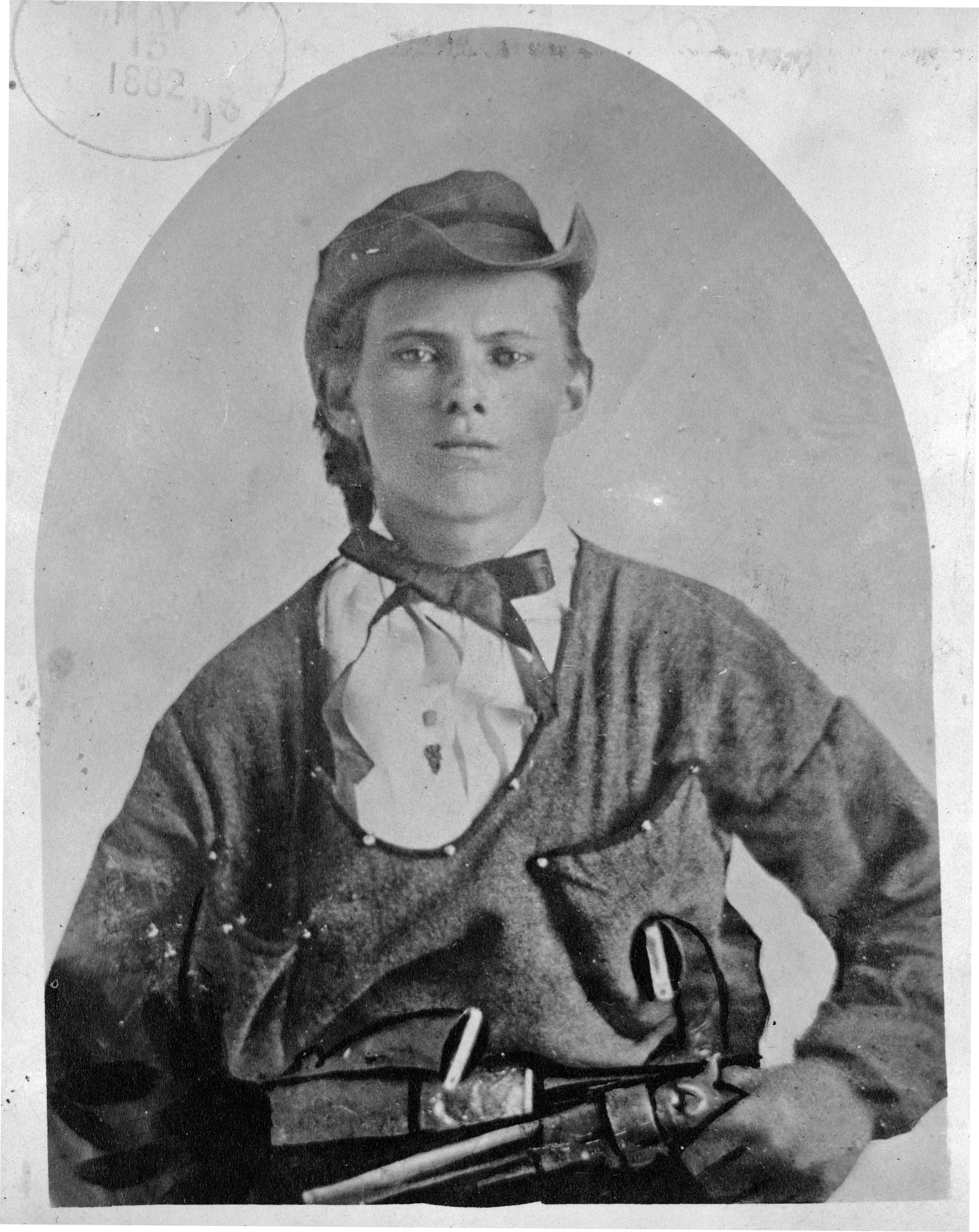

Billy the Kid and the Regulators

Billy the Kid and the Regulators

IMAGE: By Ben Wittick (1845–1903) (Billykid.jpg) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. NOTE: Original image, widely circulated, was a mirror image due to the ferrotype process used to create it, leading to the erroneous belief that Billy the Kid was left-handed.

In the spring of 1876, a young knockabout jailed for petty theft broke out of a New Mexico jail and fled to Arizona. His name was Henry McCarty, also known as William H. Bonney, and he was seventeen years old– just a kid. Billy the Kid.

By the time he returned to New Mexico in 1878, a posse led by Sheriff William Brady of Lincoln, New Mexico had captured and killed a young Englishman by the name of John Tunstall. Tunstall had posed an economic threat to a pair of businessmen who basically controlled Sheriff Brady. Tunstall’s ranch-hands banded together to avenge his death and to battle what they saw as corruption in law enforcement, namely Sheriff Brady. The group formed the core of a gang known as the Regulators. Young Billy the Kid joined up.

The Regulators gained legitimacy when Justice of the Peace Wilson issued warrants for the arrest of those involved in Tunstall’s murder and sent the Regulators after them. However, Territorial Governor Axtell then decreed that JP Wilson was illegally appointed, throwing all of his acts including legalizing the Regulators into question. The Regulators went from lawmen to outlaws overnight.

Fighting broke out between the Regulators on one hand and Sheriff Brady on the other, in the end escalating to a conflict that came to be known as the Lincoln County War. By the time it ended six months later in July 1878, the entire countryside was deeply divided into factions. Billy the Kid, still a teenager, had become firmly entrenched on the wrong side of the law, but on the right side of a romantic public’s opinion.

Aided by colorful if fanciful stories about him in the Las Vegas (New Mexico) Gazette and the New York Sun, Billy’s legend grew. He had killed over 20 men, it was said, but it is probable that he was credited with many killings performed by other members of the Regulators.

In April 1881 he was captured, tried, and convicted of the murder of Sheriff Brady; he was sentenced to hang in May. Instead he escaped, killing two deputies in the process. After a two-month manhunt he was again cornered and this time killed by Sheriff Pat Garrett. Such was his popularity as a folk hero, however, that rumors still abound that he escaped that time, too, to vanish into a secure and anonymous obscurity for the rest of his days.

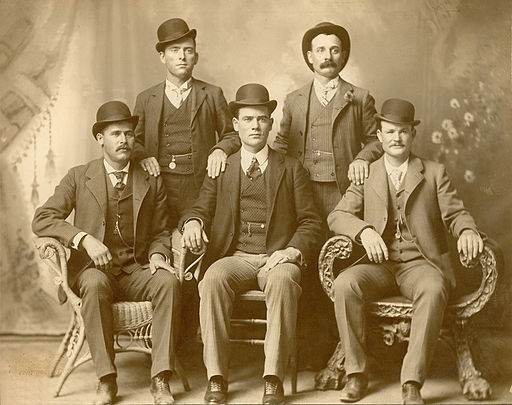

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (Wild Bunch)

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (Wild Bunch)

Robert Leroy Parker, better known as Butch Cassidy, came from a Mormon family in Utah. He adopted the name “Cassidy” in honor of a friend and mentor he met in his early teens; he acquired the nickname “Butch” from a short stint working as a butcher in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

Cassidy started his criminal career robbing a bank in Telluride, Colorado, in 1889. He moved on to ranching, possibly to create a base of operations for cattle rustling, horse stealing, and running protection rackets; in 1894 he was arrested for horse theft. After serving 18 months of a 2-year sentence he was released and pardoned, but eight months later was back robbing banks, this time in Montpelier, Idaho. Shortly afterwards he recruited Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, known as the Sundance Kid from his arrest in Sundance, Wyoming, into his gang. They took on the name “Wild Bunch”, a tip of the hat to the Doolin Gang whose founder, Bill Doolin, was killed the same year.

The two men and their gang continued bank and train robberies until 1901, when they relocated to Buenos Aires, Argentina and purchased a ranch there. They had only a few months of relative peace before the authorities located them and they moved on, resuming their life of crime. In 1907 they fetched up in Bolivia, still trying to establish a ranch. A year later they robbed a mine payroll, and while on the run were cornered and presumably killed by a small detachment of the Bolivian Army.

Their bodies were never definitively identified, and as with other bandits of the Wild West rumors circulated for years that they had in fact survived and were living quietly somewhere on the ranch they had always longed for.

Hole-in-the-Wall Gang

Hole-in-the-Wall Gang

IMAGE:By Bureau of Land Management [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Strictly speaking, the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang wasn’t a gang at all. It was a coalition of gangs that more-or-less roomed together atop Hole-in-the-Wall Pass in Johnson County, Wyoming. The area was a natural fortress, easily defended and having clear sight-lines in all directions.

A number of gangs, including Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch, took up residence there between robberies. The hideout became a bustling community; each gang provided its own cabins, livestock and supplies, while the gangs shared common facilities such as a corral and livery stable. The gangs co-existed peaceably for over fifty years, reserving their anti-social activities for the so-called ‘civilized’ outside world.

“Black Bart” – Charles Bolles (or Bowles)

“Black Bart” – Charles Bolles (or Bowles)

No listing of Western outlaws would be complete without at least a brief entry on Black Bart, the gentleman bandit, Beau Brummel of western desperadoes and self-styled “Poet”.

Before the Civil War he was a settled family man, living with his wife and four children in Decatur, Illinois. When the war began he enlisted with the Union forces and served honorably, returning to his family when the war ended. Two years later he caught gold fever and went prospecting in Idaho and Montana for a few years. In 1871, he told his wife that he had had an “unpleasant encounter” with some Wells Fargo agents; he left to settle the score and she never heard from him again.

Instead, he set out on a string of robberies– 28 in all– of Wells Fargo stagecoaches in Northern California. As a bandit, he had style and class. He dressed well, in a long linen duster and bowler hat; he was polite, well-spoken, and never used profanity during his robberies. He carried a shotgun but never used it; the subtle threat was enough. On two occasions he left ‘poems’ at the robbery sites, little bits of wry doggerel that earned him the ‘poet’ designation.

He was eventually caught by two Wells Fargo detectives and served four years in San Quentin prison. He was last seen on February 28, 1888 and rumors circulated that Wells Fargo had given him money to retire on, perhaps easier and cheaper than having him resume his life of crime. Wells Fargo, of course, denies this.

FURTHER READING AND OTHER REFERENCES

BOOKS

Wllman, Paul I. A Dynasty of Western Outlaws. University of Nebraska Press, 1961.

Stewart, George R. Committee of Vigilance: Revolution in San Francisco, 1851; an Account of the Hundred Days When Certain Citizens Undertook the Suppression of the Criminal Activities of the Sydney Ducks. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1964.

Dan De Quille (William Wright). The Big Bonanza. Hartford, CT: American Publishing Co, 1876.

James, Ronald Michael. The Roar and the Silence: A History of Virginia City and the Comstock Lode. Reno and Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press, 1998.

WEBSITES

“Correcting Recent Bodie Myths: Let’s Set the Historic Record Straight”, Michael H. Piatt, www.bodiehistory.com/myths.htm

Portal to Texas History, “Belle Starr” date:1850-1900

National Police Gazette (Since 1845), http://policegazette.us/

Wikipedia: List of Old West gangs, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Old_West_gang

(Posted July 2016)