SELF-POWERED

On Foot

On Foot

Until the 1800s, common people got around on foot for the most part. Animal-drawn vehicles were usually reserved for the transportation of goods and for the convenience of the very wealthy.

The earliest public transportation was by water, such as ferries and canal boats; urban transport such as horse-drawn buses did not appear until the 1660s.

Bicycle

Bicycle

Wheeled transportation of a personal nature (bicycles and roller skates) did not become popular until the 1870s due primarily to the nature of the road surfaces available.

Although asphalt (a crude petroleum product) had been known since prehistoric days, its use as a road surface did not occur until the 1870s. Prior to that roads were constructed of packed dirt, cobblestone, or wooden planks. All were manageable for the spring-mounted wagons and carriages of the day, but were too rough for bicyles or roller skates.

After the 1870s, however, these ‘personal wheels’ gained rapidly in popularity.

Roller Skates

Roller Skates

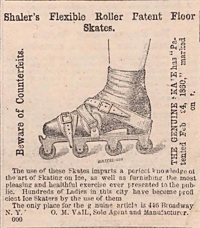

The first known roller skates appeared in the mid 1700s and were basically just ice skates with a single line of wheels where the blade would normally go.

In 1863, Massachusetts native James Plimpton invented the ‘quad skate’, with two sets of two wheels each. The four wheels provided additional stability, and the axle design allowed for easier turns. His design came to dominate the industry, and is still in use today. The adjustable-length, clamp-on skate was developed in the early 1900s by John Jay Young of New York City.

In-line skates did not return to popularity until the 1960s with the introduction of the ‘rollerblade’.

ANIMAL-POWERED

Horseback and Muleback

Horseback and Muleback

Horses and mules were the primary means of personal transportation in the 1800s, next to ‘Shank’s mare’ (walking). Due to the expense of maintaining each animal, however, individual riding animals were less favored than those pulling vehicles.

The exception, of course, was where speed and agility were most important, such as herding cattle, or where distances needed to be covered quickly. A good horse at a walk over reasonably level ground could travel at 4 mph for hours, covering perhaps 50 miles per day. On good ground, at a trot, the same horse could travel at 8 mph and if pushed could cover up to 80 miles per day.

The debate regarding the relative merits of horses and mules continues to this day. The two are very similar in most respects, but mule aficionados claim that their mounts are hardier, more intelligent, stronger, and more sure-footed than horses. Horse fanciers, on the other hand, claim that their animals are more biddable, handsomer, quicker, and of course more fertile (the hybrid mule is a sterile animal.)

Horse- or Mule-Drawn Wagon

Horse- or Mule-Drawn Wagon

Horse- and mule-drawn wagons and carriages could cover 15 to 25 miles per day on reasonable ground. They were substantially faster than ox-drawn wagons (5-12 mph compared to 1-2 mph for oxen) and hence were used exclusively when speed was needed over distance, or for in-town use.

Special horse breeds were developed for draft (heavy pulling) use. The most common breeds in the United States were Belgians, Clydesdales, Percherons, and Shires; by 1900 there were more than 27,000 purebred draft horses in the U.S. They were used to haul heavy freight across country, pull horse-car trolleys in the cities, rush fire fighting equipment to fires, pull plows on the farms, and walk hearses to cemetaries.

IMAGE: By Jean (originally posted to Flickr as American Belgian) via Wikimedia Commons Http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0.

Ox-Drawn Wagon

Ox-Drawn Wagon

Oxen were much slower than either horses or mules, and the structure of their hooves made them all but useless on slippery or frozen ground.

They were, however, far superior in cost, strength and stamina. A team of oxen cost half as much as a comparable team of horses; they required half the feed and could subsist on poorer fodder than either horses or mules. They were also stronger, and could pull a load four times that that a horse team could pull.

Something over half to three-quarters of the immigrant wagons travelling to the West Coast were pulled by oxen.

Stagecoach, Omnibus and Horsecar

Stagecoach, Omnibus and Horsecar

Stagecoaches ran regular routes (usually long distance) at scheduled times; advance reservation and ticket purchase was required. Omnibuses were the local version of the stagecoach, except that passengers could simply get on and off as they pleased with no advance booking required. Horse-drawn trams (also known as horsecars or horse-drawn streetcars) travelled on iron or steel rails, which gave a smoother ride and required less effort on the part of the horse.

The concept of horse-drawn ‘mass transit’ arrived relatively late in history. Stagecoach routes began in England in the mid 1600s. They were first seen in the United States in the mid-1700s, and with the development of macadamized roads the routes spread rapidly. The familiar Concord coach was first produced in 1827.

Omnibuses (or horse buses) first began operation in England in 1824 and in New York in the late 1820s. The first horsecar trams for passengers originated in Wales in 1807 and started in the U.S. in New York on November 26, 1832.

Cablecar

Cablecar

Contrary to popular belief, the cable car did not originate in San Francisco. The first known cable car for transporting passengers was built in England in 1826, and a version of the system was used in London in 1840 and New York in 1868. However, the rope used in these systems was prone to wear and the systems closed after a few years of operation.

In 1873 Andrew Smith Hallidie tested a system which used an improved gripping mechanism and wire rope. The resulting system was sucessful and formed the basis of the iconic San Francisco cable car system in operation today.

IMAGE: By Ronnie Macdonald from Chelmsford, United Kingdom (San Francisco Cable Car 17 Uploaded by russavia) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

BY WATER

Canal Boat

Canal Boat

Canal boats and barges were the earliest forms of water transportation. The boats were propelled by pole or, more often, pulled along the river or canal by horses or teams of men.

Clipper Ship

Clipper Ship

Like the Pony Express, the clipper ship was born of a passion for speed, served admirably for a short period of time, and then vanished from the scene when the circumstances that gave rise to it changed.

The ‘clipper’ was a fast freight-carrier that was developed on the Eastern seaboard; the first generally-recognized ship of this class was the Ann McKim, built in Baltimore in 1833. Other, larger ships of the same caliber followed, spurred on by the need for swift communication with distant San Francisco during the Gold Rush days. The Gold Rush was largely over by 1859 and the building of clipper ships in the U.S. ended at about the same time.

Ships of the clipper type remained in service throughout the rest of the world, and British ships were built for the China tea trade. In 1869, however, the Suez Canal opened and steam ships took over the trade. The day of the beautiful, graceful clipper ship was over.

Steamship or Steamboat

Steamship or Steamboat

“Steamship” usually refers to a steam-powered ocean-going vessel, while “steamboat” more often refers to a similar vessel plying lakes or rivers.

Steam engines were first developed in the early 1700s, but it was not until the early 1800s that commercially-viable steamboats came into operation. At first they served on inland waterways as ferries, but by 1813 steam-powered vessels were navigating portions of the North Sea off England.

Most inland vessels used a stern-wheel paddle, while ocean-going ships used side-wheel paddles. In 1839 the first screw propeller was developed, but did not really catch on at first because the screw action caused excess stress on the wooden ships of the day. When iron became common for ship construction in the 1860s, screw propellers gained in popularity as well.

MACHINE-POWERED

Railroad

Railroad

Although rails had been used to reduce the effort needed to move heavy loads since the 6th century B.C., it was not until the late 1700s that William Murdoch, a Scottish engineer, built a prototype steam locomotive.

The first full-size, working steam locomotive was built by the Englishman Richard Trevithick in 1804. The first American locomotive, the Tom Thumb, made its debut in 1830. The rail network in the U.S. spread quickly, and by the time of the Civil War had become crucial for transportation of men and supplies.

It was clear that rail transportation was faster, cheaper, and more reliable than overland by coach or wagon, or by ship to the Pacific coast. As a result, the first transcontinental railroad was commissioned in 1862 and completed in 1869.

Automobile

Automobile

The first self-propelled motor vehicle was actually a steam tricycle built by the Frenchman Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot in 1769. Numerous steam-powered vehicles were developed over the next 40 years, but were inefficient, unreliable, and not infrequently dangerous.

Various fuels were tried, including a hydrogen car in 1807, developed by the Swiss engineer François Isaac de Rivaz, and a car running on a mixture of moss, coal-dust and resin, invented by Frenchman Nicéphore Niépce in the same year. A fully-functional electric automobile was built by the French inventor Gustave Trouvé in 1881, but again was viewed primarily as a novelty.

Karl Benz, the German engineer, is generally viewed as the inventor of the modern automobile. In 1879 he patented an internal combustion engine, and in 1885 built his first Motorwagen.

The first production-line automobiles were built in the United States by Ransom Olds in 1902. Henry Ford greatly expanded the idea beginning in 1914, and is often if erroneously credited with the assembly-line concept.

IMAGE: 1888 Flocken Elektrowagen By Franz Haag (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

FURTHER READING AND OTHER REFERENCES

California Draft Horse and Mule Association, http://www.cdhma.org/

National Museum of Roller Skating, http://www.rollerskatingmuseum.com/

Wells Fargo History Museum, http://www.wellsfargohistory.com/

MacGregor, David R. Merchant Sailing Ships 1850-1875. Naval Institute Press (March 1985)

(Posted July 2014)