COINS AND CURRENCY

Paper Money

Paper Money

From 1837 (when President Andrew Jackson refused to renew the charter of the Second Bank of the United States) until the beginning of the Civil War, there was no central Federal bank. Currency was instead printed and circulated by various state-chartered banks, financial institutions, and in some cases even hotels and restaurants trying to make change for larger denomination bills offered by their customers. By the mid-1850s, there were more than 10,000 kinds of bank notes in circulation, varying in size, denomination, design and value.

This decentralized system gave rise to rampant counterfeiting and a complex system of discounting instruments’ face value depending upon the distance from the issuing institution, ratings of the institution in multiple publications dedicated to pricing currency in circulation, and in some cases the perceived respectability of the individual making payment in the currency. In the western United States, cut off from the rest of the country, paper money was highly suspect and transactions were frequently paid for in coin, bullion, or even gold dust.

When the Civil War broke out, the Union needed to raise funds quickly. It did so in 1861 by authorizing Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase to borrow money and issue federal “notes” in exchange. In 1862 the system was further refined by creating two types of currency, “notes” which were redeemable for gold or silver, and “legal tender”, which was in essence unsecured. The two notes looked very similar, and both were called “greenbacks” due to the color of the printing on the reverse of the notes.

In 1863 the National Banking Act was passed, establishing federal bank charters, and many banks surrendered their state charters in favor of the new federal charters. By the end of the war, there were 349 state and 1,294 national banks in the United States. This law also established a system of federal bank notes, issued by the newly chartered federal banks, but differing from one bank to another only by a printed identification of the issuing bank at the top of the note.

In 1865, the federal government effectively ended the state bank practice of issuing currency by the simple expedient of placing a 10% tax on all such currency. Unable to compete with federal notes trading at 100 cents on the dollar, state banks discontinued issuing currency and instead turned to traditional banking pursuits such as taking deposits and making loans. Federal banks were initially prohibited from making loans, so state banks rebounded and by 1892 the number of state and federal banks were about equal.

Because coins were scarce and often worth more than paper money, bills in denomiations smaller than $1.00 were in circulation during the Civil War and for some years afterwards. These bills were issued in face values of 3, 5, 10, 15, 25, and 50 cents.

Coins and Coinage

Coins and Coinage

“Specie”, or money in the form of coins, was valued over paper money for much of the 1860s and 1870s. As the original U.S. coins were made of pure or nearly pure gold, silver or copper, the intrinsic value of the metal bolstered the acceptance of the coins and led to hoarding during the Civil War.

Coins were originally minted in eagles ($10, $5, and $2.50 denominations in gold), dollars ($1.00, $.50, and $.25 denominations in silver), dimes or “dismes” ($.10 and $.05 denominations in silver) and cents ($.01 and half-cent denominations in copper). During the Gold Rush a double-eagle ($20) was added; formal acceptance of the Spanish coinage as legal U.S. tender was revoked at the same time. During and immediately following the Civil War, coins in 2-cent and 3-cent denominations were minted, as were the now-familiar nickel and a $3 gold piece.

Coin sizes and face designs varied over the same period, originally the same design for all denominations and later separate designs for each denomination. Metallic composition also changed over time, reflecting changes in gold and silver prices as well as war-related shortages of nickel and copper.

CURRENCY/COMMODITY EXCHANGES

New York Gold Exchange

New York Gold Exchange

When the Civil War broke out, gold trading on the New York Stock Exchange was banned as “unpatriotic speculation.” Not deterred, gold traders merely moved operations to various basement locations near Wall Street. Congress reacted by prohibiting gold trading entirely, but repealed the law again two weeks later. Finally, the informal gold exchange was incorporated separate from the Stock Exchange on October 14, 1864, under the name “New York Gold Exchange.”

Although the Exchange did have some legitimate purposes in management of foreign trade, it primarily engaged in currency speculation in the new federal “greenbacks.” Trading on the Exchange was wild, with massive profit and loss swings and high bankruptcy rate. Deliveries were short, late, and not infrequently adulterated. Nonetheless, the Exchange prospered in the post-War climate, and in 1865 again merged into the New York Stock Exchange. Gold speculation continued as a destabilizing element in the economy, and contributed significantly to the Black Friday panic of 1869.

San Francisco Mining Exchange

San Francisco Mining Exchange

The San Francisco Stock and Exchange Board was formed on September 11, 1862 and initially dealt in buying and selling of all kinds of financial instruments: greenback/specie currency exchanges, city indebtedness, transportation stocks, local trolley lines, utility companies and so on. Soon, however, it came to specialize in mining stocks and from time to time was known as the San Francisco Mining Exchange.

In its heyday it was, strictly speaking, not a stock exchange nor did it deal in commodities. It actually facilitated the buying and selling of “feet”, equal to a fractional interest in the linear footage of a mining claim (usually 100 feet or multiples thereof). It was only later in the evolution of trading that “feet” were translated into actual mining company shares.

Initially the Exchange was viewed as a wildly speculative venture, and merely trading on the Exchange was enough to unhinge the credit rating of the trader. Soon, however, it had become so well established that at its height in the 1870s its daily volume exceeded that of the New York Stock Exchange.

BANKS AND BANKING

California Banks

In classic San Francisco style, banking in the city began with a wild and somewhat decadent flourish. On January 9, 1849, Henry M. Naglee opened the short-lived Exchange and Depot Office on Kearny Street, adjacent to the Parker House, a popular gambling spot. There he dispensed cash and whiskey with equal abandon, the bar being only a few feet from the safe. In less than two years, having had his fill of high finance if not whiskey, Naglee retired to manufacture high-end brandy in San Jose. His firm was, however, followed in quick succession by other banking firms.

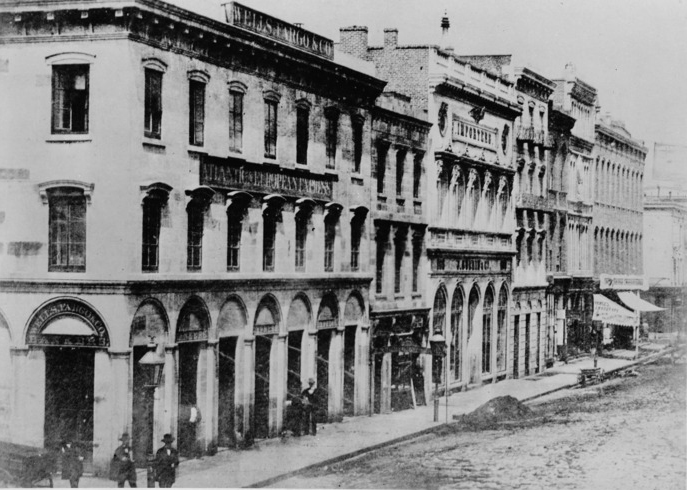

Wells Fargo Bank

Wells Fargo & Company began life primarily as an express company (rapid delivery of the gold and anything else valuable). That business remained its primary focus for decades, while traditional banking (buying gold and paper bank drafts, taking deposits and making loans) was added on later as a way to facilitate and expand its core business. Wells Fargo was formed in New York on March 18, 1852 by Henry Wells, William Fargo and other investors.

The newly fledged firm opened its offices in San Francisco and Sacramento, California, in July of 1852. In 1858 it joined with a number of other express companies to form the Overland Mail Company; Wells Fargo surveyed the 2,757–mile route. The “Butterfield Line”, named for the company’s president, John Butterfield, was born. Wells Fargo soon expanded into the pony express mail service, and ran a route from San Francisco to Virginia City, Nevada, until 1865.

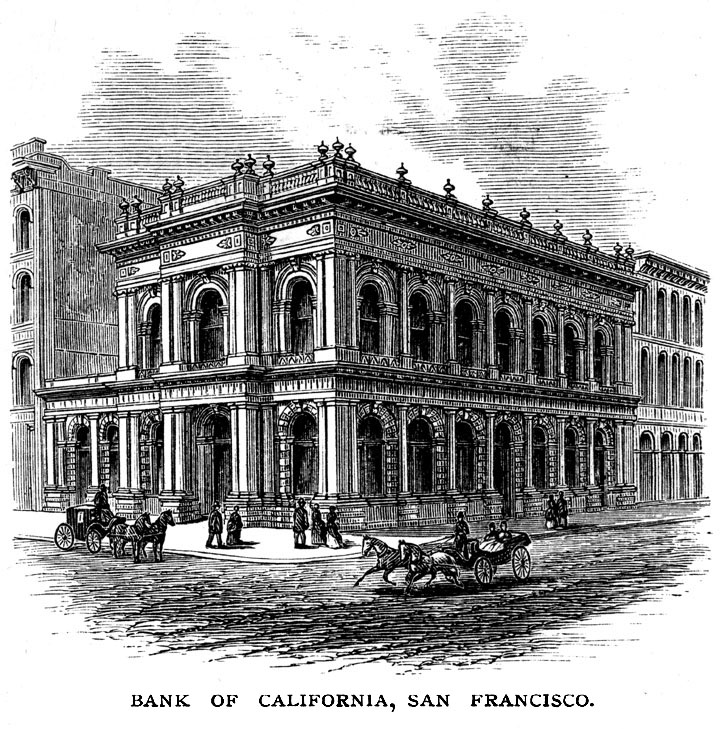

William Chapman Ralston opened the Bank of California in San Francisco, California, on July 4, 1864. The Bank’s ancestor was the banking firm of Garrison, Morgan, Fretz & Ralston, established in San Francisco in January 1856.

The firm moved rapidly and aggressively to establish itself in San Francisco, then two months later springboarded into Nevada (see below).

Anglo-California Bank

The Anglo-California Bank was incorporated in 1873, successor to the firm of J. Seligman & Co., which had previously done banking business in San Francisco. That firm itself was an expansion of a mercantile business that had opened in 1850. Ignatz Steinhart, a Bavarian immigrant, and D. J Seligman, principal in the predecessor firm, were the first founders.

By 1876 the Anglo-California Bank was one of the top four banks in San Francisco. It continued to prosper, and through a series of favorable mergers ultimately became Crocker National Bank. In 1986 it was acquired by and merged into its former arch-rival, Wells Fargo Bank.

Nevada Bank of San Francisco

In 1875 the Bonanza Kings (John William Mackay, James Graham Fair, James Clair Flood and William S. O’Brien), the richest men on the Comstock Lode, formed the Nevada Bank of San Francisco. The same year they built the bank’s headquarters, Nevada Bank Building on Pine and Montgomery. The building was luxuriously appointed with quartz fireplaces shot through with veins of gold, and legend has it that some tenants rented in the building just so they could chisel the precious metal out of the fireplaces.

With the backing of the Bonanza Kings the Nevada Bank prospered at first, becoming one of the top four banking institutions in the city within the first year of operation. However, as the fortunes of the Comstock waned so did the fortunes of the bank, and by 1890 the bank was nearly insolvent. Under the guidance of the shrewd banker Isaias W. Hellman the bank’s reputation revived, and in 1905 the Nevada Bank was merged into Wells Fargo.

Nevada Banks

The financial worlds of San Francisco and Virginia City were inextricably linked, in essence two sides of the same coin. It was therefore not surprising that the Virginia City banks were primarily just branches of the San Francisco banks of the day.

The first bank in Nevada was, not surprisingly, Wells, Fargo & Co. Express and Banking Company. In 1860, one Captain Simmons was transferred to Virginia City to add banking to their express business there. Although they did no lending at that location, they did take in deposits, opened accounts for profitable mines, and discounted drafts for mining companies with established reputations.

The lead of Wells Fargo was soon followed by Stateler & Arrington, a bank that did in fact make loans, at a mere ten percent… per month. Gould & Curry Mining Company, then the largest mining company in Nevada, did all their business with that firm.

A number of smaller banks followed in rapid succession, and in 1863 a banker’s association was formed to establish uniform methods of doing business. Among other things, the association established a more modest interest rate for loans– only five percent per month.

Bank of California

Barely two months after its inception in California, Bank of California opened a branch in Gold Hill, Nevada, near Virginia City, on September 4, 1864. William Sharon, a cold and shrewd individual with unerring instincts for acquisitions, served as the bank’s Nevada agent. Under his leadership, the bank’s primary business began to look less and less like banking and more and more like mining.

The Bank made a series of loans to mines on the Comstock Lode, later foreclosing on them and acquiring substantial holdings on the Lode. The Bank continued to expand aggressively into the silver business, only to fall prey to a bank run on Thursday, August 26, 1875. The founder and Bank President Ralston died the same day and the firm fell into bankruptcy. When it reopened its doors six weeks later, it remained both a major financial player and the most important banking institution in San Francisco. However, it never regained its virtual monopoly in the San Francisco and Virginia City mining arena.

Nevada Bank of San Francisco

A branch of the Nevada Bank of San Francisco opened January 10, 1876 in Virginia City, Nevada, in the former offices of the banking firm of Paxton and Thornburg. It was a smaller player in the Comstock Lode financial scene, but continued to serve the community for twenty years until the branch closed in 1895.

FURTHER READING AND OTHER REFERENCES

Books

Van Ryzin, Robert R.. Crime of 1873: The Comstock Connection. Krause Publications (February 2001).

Website

“Wells Fargo History,” (c) Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. https://www.wellsfargohistory.com/history/

(Posted December 2016)